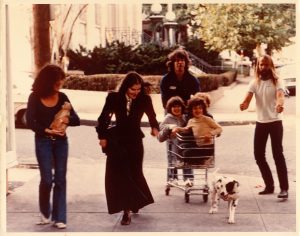

We were NOT 6 feet apart then!

I left Hollywood, California, very early on the morning of March 25, 1970, boarding a non-stop flight to JFK. One of many million long-haired hippies inhabiting the US of A at that time, I had a precious cargo with me. Very bulky and heavy, my freight was evenly divided between two big trunks on wheels. Somehow, days earlier on the phone, I had firmly convinced the airline staff that this cargo was so valuable, it could not, nor should not, be stored in the hold with the rest of the baggage. I was transporting a unique saga of the 1960s with me. As one of two producers (the Associate Producer) of the movie Woodstock, one of my last obligations was to get the finished films to the two movie theaters in New York City for the opening press and audience screening on the afternoon of March 26, 1970. We had manufactured eight prints: 2 for Los Angeles, 1 each for Chicago, Atlanta, San Francisco, Toronto, and my two for NYC.

I landed on schedule, found a taxi with a large enough truck to carry the two trunks, and we made our way to mid-town Manhattan. Crowds were already gathering outside the Trans-Lux West on Broadway where I unloaded one trunk. A Warners PR person was on hand to take the second to the Trans-Lux East. Hundreds of people were lining up in the streets. “You’ve got the actual movie there in those cans?” I was asked as I pushed my way. Yes, I said to myself nervously. I could almost hear the soundtrack reverberating among the crowds. Richie and Jimi, Country Joe and the Fish, Joan Baez and John Sebastian. Arlo, Ten Years After, Sly and the Family Stone. And Joe Cocker, The Who, Carlos Santana with Mike Shrieve the drummer, and Sha-Na-Na, the 1950s dance troupe. And, of course, Max Yasgur, the Port-O-San Man, and Wavy Gravy.

Their voices could soon be heard in Manhattan, surrounded by the hundreds of thousands of young people who had gathered for peace, love, and music in one of the most spontaneous happenings the world has ever known. Their story was three hours and four minutes long. Their stories live a lifetime, even today and tomorrow. They made history, protesting the Vietnam War, struggling in the civil rights streets, where women’s rights and gay rights and human rights clashed like musical chords in the night. Voices, words, and music created a harmonious community that still bonds. We who had made the film—on Max’s farm for 6 days, in the editing rooms for eight months, moving everything four times before we were finally finished on the Warners lot, knew every frame, every sequence, every sound, every stitch of music, dozens of times over. They were our family, and our own production and editing family had extended from nearby Zabar’s Deli on upper Broadway to Hollywood, then to Burbank where the Warners lot was empty. And what a family we were. Almost one hundred people on both coasts had helped us to make this film. And here was our movie, in a trunk, on its way to the projection booth, eager to get out and show off. No one was 6 feet apart!!!

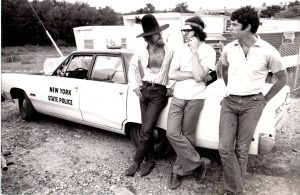

Michael Wadleigh (Director), Bob Maurice (Producer) and Dale Bell at Woodstock

The movie would restore Warner Brothers, become the most profitable film of 1970, yield the highest grosses ever made for a documentary, win the Best Feature Documentary Academy Award in 1971, and bring a nomination for Best Editing to Thelma Schoonmaker, and Best Sound to Dan Wallin and L.A. Johnson, while receiving standing ovations around the world. No critic could ignore it. Nor could the millions globally who became and have remained devoted fans because of its music, its humanity, its technology, its universal scope, and it’s many voices. Woodstock the movie matters—then, now, and for our futures. Leverage it. We meant it.

DALE BELL, Associate Producer, Woodstock the Movie